Tips and Tricks for Using Design Thinking in the Classroom.

In Oscar-winning director Christopher Nolan’s 2010 metaphysical-heist film Inception, characters use shared dreaming to commit corporate espionage. About midway through the film they’ve infiltrated the subconscious of their mark and find themselves trapped in a warehouse, as projections designed to protect the subject’s secrets close in on them, armed to the teeth. Tom Hardy’s Eames and Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s Arthur attempt to fight them off as the team engineers a plan for escape. While exchanging fire with the army of projections, the suave and smarmy Eames tells the buttoned-down Arthur, “You mustn’t be afraid to dream a little bigger, darling.”

I think about this moment often in my work, and not just because I’m an unabashed fan of Nolan’s films, this one in particular. Facing impossible odds, with little hope of escape, the solution offered up by one of the protagonists is, dream. Manifest the solution to the problem that faces you. We can only ever become overwhelmed by a challenge if we give up trying to get around/over/through it.

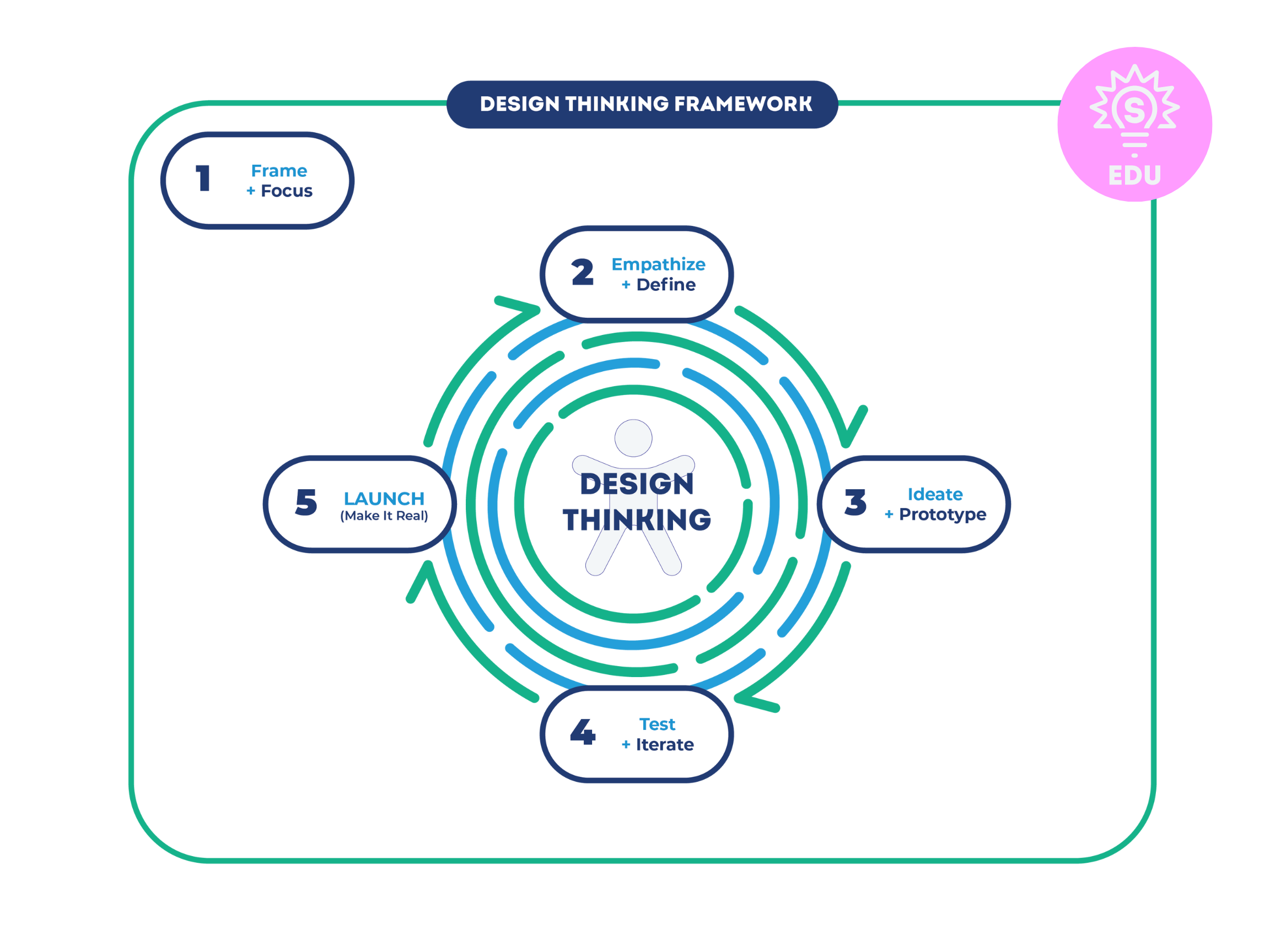

In working with teachers to implement Design Thinking in their classrooms, there are many moments where they feel stuck, challenged, or incapable. Usually in these situations they are being confronted with some aspect of their projects not going according to plan. While Eames’ solution to Arthur is inspiring, I think it might be helpful to point out some common struggles at each stage of the Design Thinking process, and offer some more concrete steps to take in order to overcome these barriers.

Frame

This stage of the Design Process provides the structure that supports designers as they try to solve problems. The Frame typically takes the form of a question beginning with, How might we…? Whatever the nature of the Design work at hand, this question stays with designers throughout the process, despite eventually being refined later.

Teachers working on framing a question during our fall Citywide Professional Development

A common misconception we’ve seen with teachers in directing this portion of the Design Process involves misconstruing the Frame Question as providing the problem to be solved. It does not. The Frame Question creates a space in which designers can discover problems. For example, teachers at Startland’s Spring Citywide training solved for the Frame Question, How might we improve teacher retention and job satisfaction? At this point of the Design Process, the problem itself is unknown. Designers have to work within the space created by the Frame Question to try to find the problem that they want to solve, because those of us working in educational spaces know that the reasons for decreased teacher retention and job satisfaction are myriad and diffuse.

Foregrounding the role of the Frame Question, as creating space to discover problems rather than providing the problem itself helps students to remain open-minded and curious as they move into the Design Process.

Empathy

The overall success or failure of the solutions that designers generate will hinge on the depth and relevance of the Empathy work they engage in. During this stage of the Design Process, designers are learning about users’ experiences in order to better understand them, enabling them to better meet their users’ needs. Without robust Empathy work, designers can’t succeed in creating meaningful solutions.

There are a couple of routine pitfalls that students will fall into during this stage. The first is falling in love with their own ideas. Human beings, by nature, believe in the primacy of their own thinking. This is especially true of adolescents, in my experience. It is common for students to focus on an area of the Frame Question that really bothers them, even though it might not be the thing that is most responsible for making life difficult for users. In a project working towards creating a better school experience for their peers, students will gravitate towards, say, lunch, as a key pain point. If they will set aside their own experience and listen to the experiences of their users, though, they’ll find that what students are typically most upset about are the aspects of school that influence the 7+ hours of their days in which they’re not in the cafeteria. Things like rules, policies, procedures, structure, and teaching strategies played much larger roles in their experience.

Another issue that pops up again and again is students’ failure to test their own assumptions. For example, “No one likes school lunch” really means, “I don’t like school lunch.” In reality, some students like school lunch, some students don’t, and some don’t have very strong feelings either way. During the Empathy phase of the Design Cycle is the time to test these assumptions, find out if they are real and valid, or if the experiences of our users indicate that students need to explore other areas.

Highlighting the importance of Empathy work in problem solving steers students away from these struggles and towards more meaningful and complete Empathy work, which will ultimately lead them towards better solutions and happier users.

Define

Once designers have a robust body of Empathy work to draw from, they can use it to narrow their focus onto a specific problem within their Frame that they want to solve for. In doing so, it’s imperative that designers are as clear as possible about what the problem is, who it affects, and why. Returning to the above example from Citywide, there are many possible Focus Questions within the larger Frame of teacher retention and satisfaction. Maybe the problem identified is overscheduling. Maybe it’s a lack of support with students in the classroom. Maybe it’s teachers being asked to spend their own money on classroom resources. To be sure, all of these are issues worthy of addressing. So how do designers arrive at the problem to solve for?

Students working to define their problem during a MECA Challenge.

The answer is leaning into their Empathy work. Sometimes students will begin their Empathy work with a problem in mind and stay married to it throughout the Empathy process, even if the information they gather through their Empathy indicates that a different area might be more important. The most successful designers allow Empathy to inform their decision making.

Another common issue students will have is a lack of clarity or specificity around their problem. Students working within the Frame of improving the school experience might say, “The problem is class is boring.” At this point, a Root Cause Analysis, or an activity like The Five Whys can help students get more specific about the problem. Why is class boring? “Because the content isn’t relevant to me.” Why? “Because teachers don’t have the freedom to be responsive to students' needs.” Why? “Because their instructional decisions are micromanaged.” Now students can write a better problem statement “The problem is that teachers aren’t able to be responsive to their students’ needs because their decisions are being micromanaged.” This is a problem statement students can Ideate to solve.

Ideation

This is the part of the Design Process that asks designers to recall and embrace Eames’ statement from Inception. Designers have to be willing to dream big, to be inspired by the awesome potential of what is possible. This has the capacity to be an opportunity to amplify excitement and engagement for students. This can only happen, though, if students get beyond the practical. Oftentimes, they fail to dream a little bigger, settling for what they think they can get instead of dreaming of what they might be able to achieve if all of the boundaries, restrictions, and barriers that impede them were removed. Students are caged birds, too close to the bars to be able to see that they are there, or fenced in dogs who fail to jump the fence for no reason other than that they believe they can’t, or that they aren’t supposed to.

There is a temptation during this portion of the process to allow students' beliefs about what they can hope for to remain limited so as to avoid a let down for them. This is counterproductive. Progress towards solutions to problems that matter requires audacious risk. If we want students to take themselves seriously as agents of change, we have to take them seriously ourselves. This is not to say that we shouldn’t be realistic about what is within their locus of control, but rather during Ideation, we only affirm or add to the solutions they have generated. Big dreams lead to meaningful solutions.

Prototype

Designers have landed on their solution and now need to develop that solution into a Prototype that they can share with others. This stage can be intimidating to students, because it is the part of the process where they are asked to make things concrete, an experience that is unfortunately exceedingly uncommon in traditional school settings. Their lack of familiarity with this process can lead students to solutions that are overly general, or lead them to fail to make specific connections between their Prototype, the problem, and the needs of their users.

During this stage, lean in and ask questions about students’ Prototypes. What is this? How does it work? How does it solve the problem? Why will users find it valuable? After this type of questioning students may revise their Prototype, realizing that their early version doesn’t answer all of these questions. That’s great! After they’ve done this, ask them all of these questions again. The line of reasoning between the problem, the market, and the solution have to be clear in order for users to embrace the Prototype. Once they have clarified this relationship, they are ready to share their Prototypes with a larger audience.

Testing

Typically the form of Testing that I’ve experienced with students involves pitching their solutions to an audience. The first and most obvious challenge that students face is the all-to-common fear of public speaking. More prevalent than the fear of spiders, heights, and even death, the presence of student anxiety around public speaking might lead some educators to back away from pitching as a part of the Design Process. I would posit that it actually suggests the opposite. Students need scaffolded opportunities to pitch through which they receive clear and direct guidance to provide them with successful public speaking experiences in order to build confidence and decrease their fears.

Students celebrating their win after pitching at our Back 2 School Challenge

In the classroom, I frequently implemented a pitch-as-you-go format, where students would soft pitch regularly throughout the process of developing their Prototypes. This type of structure created a lifeboat mentality for students, one in which they were supporting each other's efforts and generous with their feedback. It also allowed students to have many pitch-like experiences along the way so that when they stood in front of an authentic audience sharing their ideas, they had some successes to draw on to ease their anxiety.

We often supply students with a sample Pitch Flow that provides a structure for them to employ in building their pitches. Typically, students have a finite amount of time to work through their pitches, and appropriately allocating this time can sometimes be challenging. Sometimes students will devise an elaborate hook before launching into a detailed description of their problem, leaving themselves very little time to share the details of their solutions. A point of emphasis, then, is to be solutions-focused when developing your pitch. Students’ hook should build a bridge to the audience and capture their attention. The focus on the problem should be an overview with enough details to convince the audience that the problem is significant and worth solving. Then the bulk of the pitch should focus on explaining the intricacies of the solution. Providing this framework and feedback to students is another way for them to experience success with pitching and build confidence in their efficacy as public speakers.

Iterate

‘Kill your darlings’ is a familiar phrase to writers. It instructs the writer that though they may love certain aspects of their work, they must be ready and willing to part with any characters, plot events, or other elements that don’t serve the overall quality of the story they are trying to tell. During the Iterate phase of Design Thinking, designers synthesize feedback gained during Testing in order to make adjustments to their Prototypes so that they can better meet the needs of their users.

If students are emotionally attached to their Prototypes, they will struggle to let go of aspects that they may love, but that do not serve their users. During this phase, I will often share stories of writers doing this. One of my favorites is the journey that led award-winning author Smith Henderson to his novel Fourth of July Creek. The writer was working on a pair of separate projects and was about 100 pages into each of them. The first was about a social worker and the second, a conspiracy-minded survivalist. The author was stuck, and made the bold move to throw out the first drafts of both projects, put the central characters of the two pieces into the same world, and see what happens. Fourth of July Creek was the result.

This is the kind of bold move that true iteration requires. If something about the project is not meeting the needs of its user, designers are compelled to move on regardless of how they may feel about it. This stage really tests the commitment of designers to solving the user’s problem. It’s one thing to suspend assumptions and work to avoid falling in love with their own ideas in the Empathy phase, when no tangible work has been done towards the solution. It can be much more difficult to move on from their own idea that they’ve put time and energy into developing, but oftentimes that is what is required to land on a meaningful solution for users.

Launching

This is designers’ opportunity to take their solution and make it real. When we work with student groups, we tell them this is when they make an entrepreneurial decision about whether or not to pursue their idea beyond the bounds of the project. Any number of factors can go into making this decision. Not every idea that an entrepreneur fleshes out ends up going to market, so I tried to make students comfortable with choosing not to Launch. There is still much to be learned in completing the process to this point, and if they don’t feel called to pursue their work further, there is no shame in that. But I worked to make one thing clear to them: you are ready, if you choose to be.

Sometimes students at this stage of the process will convince themselves otherwise. They will fail to follow Eames’ advice and dream a little bigger. They’ve convinced themselves that they are not capable or prepared. Despite the process that they’ve completed and the success they’ve experienced, they are still under the impression that entrepreneurship is something other people do, that it’s not for them. Sometimes due to socioeconomic, gender, or racial stereotypes, they think that entrepreneurship is for other types of people.

By the time their projects are culminating, we’ve typically developed a strong relationship with our designers, and so we work to leverage that in our messaging to them. At this point, designers are already entrepreneurs. They belong in this space, and are equipped to make whichever decision they feel called to. If the wish to press on is within them, we work to empower them to follow that inclination as far as they possibly can. We’ve had interns incorporate nonprofits, develop social events, and launch influencer campaigns based on their work in our internships. Whether they choose to pursue their ideas or not, though, the central thing for us is that they know what they are capable of.

If you’re interested in taking your entrepreneurial projects with students to the next level, consider exploring the new Entrepreneurial Teaching Accelerator, sponsored by The Kauffman Foundation and facilitated by Startland Education this summer. You’ll get practical ways to implement all of the strategies described above, high-quality professional development in human-centered design, and a tailor-made curriculum developed to facilitate entrepreneurial projects in the classroom across contents. Click here to learn more and sign up.

Ready to rethink teaching and learning in your community?

Contact Startland Education to hear how we can help.