Feedback Vs Grading: How design thinking creates a feedback driven classroom

After the dismissal bell released my seventh period class, I was stumbling through rows of desks, clearing out my room when I saw it. While gathering abandoned Takis bags and half-empty bottles of Diet Coke, winding my way through chairs that hadn’t been pushed in, I discovered my own handwriting in purple ink looking up at me from the crumpled essay that had been discarded on the green linoleum floor. After my English III classes had devoted 2 weeks to completing these essays, I spent hours providing individual, specific feedback before scribing scores across the top and returning them to students. And here, a student had unceremoniously cast their essay aside, like Travis Kelce shucking a Los Angeles Chargers defensive back on a fourth quarter whip route..

In talking to both students and colleagues over my 15 years as an English Language Arts teacher, I’ve gathered differing perspectives about how and why this practice of delivering feedback to students breaks down. One thing I’m certain of, though, is that this is standard procedure for many participants in the school system. Students submit work that is then evaluated using a combination of notes and scoring before being returned. This process is incredibly time-consuming for the teacher, but we justify that expenditure by telling ourselves students will read our notes and use them to improve future performance. We believe that this process facilitates student growth.

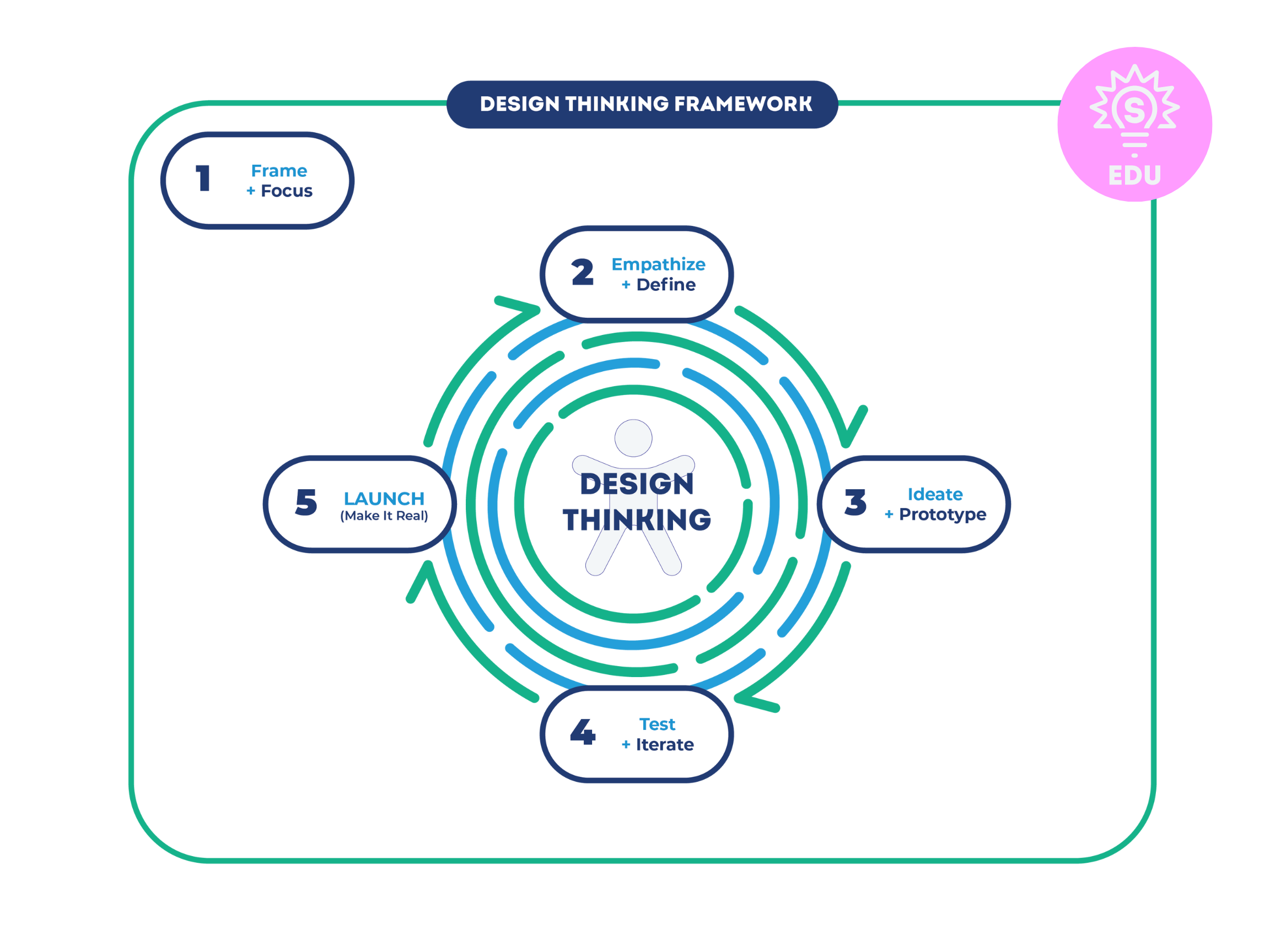

Through engaging in empathy work, the foundation of human-centered design, - one of the most important parts of design thinking - it became clear that unfortunately this was rarely happening with my students. Even those who were accomplished users of school informed me they rarely read teacher comments on their work. Of course there were exceptions, but by and large, most students looked at the top for the score, felt satisfied or irritated, pitched the assignment, and went on about their day.

There are many factors at play here, but a few I find especially significant: the grade at the top of the paper unquestionably disrupts learning, and unsolicited feedback on compulsory work can feel intimidating.

Grades and Learning

In his 2011 book Embedded Formative Assessment, researcher Dylan William describes a 1988 study of sixth graders in Israel, which I regularly referenced when discussing my grading practices and policies with my students. Williams examined a scenario where students were divided into three groups and given an academic task to complete. Researchers collected each group’s work, privately scoring all of it before returning to the students. Each group received different scoring, though; Group 1 received only a grade, Group 2 received only feedback, and Group 3 received both.

A period of time later, the students were given a similar task to complete, and their work was again collected and privately scored by the researchers. Additionally, all students were asked if they wished to continue doing similar work in the future - the researchers were interested in seeing how the differing approaches when responding to student work impacted future performance as well as attitudes about the work itself.

The results from Groups 1 and 2 were fairly predictable. Group 1 made no collective progress, and only students receiving high scores indicated a desire to persist with the work. Group 2 improved on aggregate 30 percent, and nearly all students indicated a desire to continue with the work. For those in education, these results are likely unsurprising. Group 2 received concrete input specific to how they might improve their performance, while Group 1 did not.

So, what about Group 3? Did the feedback they received empower them to replicate Group 2’s growth? Sadly, they were virtually indistinguishable from Group 1. On average, students in Group 3 did not improve, nor did they indicate an inclination to pursue this work further. Observing these results, William noted, “If teachers are providing careful diagnostic comments and then putting a score or a grade on the work, they are wasting their time.” (William 109). Simply put, grades occupy an unearned position of primacy for all stakeholders involved in the school system - one we should collectively reconsider.

William’s study resonated with many of my students. They shared with me that if they received a satisfactory score on their assignment, whether that was an A or a D, they felt they didn’t need to read the comments. And if they scored lower than they expected or hoped, they didn’t want to. By the time students arrived in my high school ELA classroom, learning had largely become a transactional proposition - completing assigned tasks in exchange for grades. It’s easy to see how learning can become secondary to the input of doing my work and output of getting my grade. Even though my intention is to encourage further learning by providing feedback on completed, graded assignments, it has often taken a backseat to their role in the transaction.

Honestly, I can empathize with my students in this scenario. There doesn’t seem to be a tangible benefit to reading my feedback. Processing the comments I give would not reduce their input or increase the output they received in return; they would still be required to do the same amount of work, and their scores on the already-graded assignments would not change. Who wants to spend any time in their day reading about all the things they did wrong when the evaluation of their work is already determined? Absent intentional, structured opportunities for revision, I have not found the concept of next time to be particularly resonant with adolescents.

I also had to consider the nature of our teacher/student relationship. My students are essentially a captive audience. They do not ask to be in my class or complete the essay assignment, nor do they ask for my notes on their work. How might what I thought was constructive criticism feel to someone in this scenario? My practice of scoring and giving notes rested on a latticework of risky assumptions, and my students’ learning was falling through the gaps. I needed a new way forward.

Toward a Feedback-Driven Classroom

As my classroom career progressed, I began chasing a system of engaging with student work that would foreground their learning, rather than the grade at the top of the assignment. In my experience students found learning to be an active process, but grading to be a passive one. They were involved in building knowledge of essential content and processes through our work together, but had no stake in the evaluation of that work. They were simply passive recipients of my judgment which took the form of grades, the currency of the transactional economy they had participated in throughout their schooling.; they were simply passive recipients of my judgment, which was the currency of the transactional economy they had been conditioned to participate in. Quickly, students learned to focus only on that judgment, short-circuiting the learning in the process.

Even items like traditional 4-point rubrics, which aim to add a level of objectivity to this process, are still subjective in their execution. For example, I had to determine whether the evidence in an argumentative writing was merely adequate, or rose to the levels of thorough or convincing, therefore deciding whether the student would score a 2, 3, or 4. Additionally, rubrics do not address the problem of the finality of the grade, or encourage students to read and internalize the feedback I provide.

I ideated several possible workarounds for this problem before discovering a couple of practices I thought could help establish the kind of feedback-driven classroom I was aiming for. On formal writing assignments, which we had a handful of times each semester, I no longer used traditional rubrics, opting instead for single-point rubrics. Single-point rubrics simplify the more traditional model, distilling the skill or content being evaluated into as straightforward of a descriptor as possible. Instead of parsing out the difference between thorough and convincing evidence, I was now asking myself, “Did this writer use evidence well in support of their argument?” If ‘yes’, the student met the criteria. The version I used contains space specifically on the rubric for things to celebrate, and areas to improve.

While Implementing single-point rubrics, I discovered another process I believed would help students engage with the feedback they were receiving on their formal writing assignments: withholding their grade. Rather than circling their numerical grade at the top of the page, or entering their scores into our online Student Information System PowerSchool, where they can see them immediately, I kept a spreadsheet to record their scores. I then returned the completed single-point rubric without the score on it. Before I would share their scores, I asked each student to complete a reflection sheet where they paraphrased the feedback received and laid out a plan for improving future formal writing assignments. After students completed the reflection sheet, I would share their current grade with an understanding that they could use the feedback to iterate and resubmit their completed work for a chance to improve their score. Before beginning our next formal writing assignment, I built in time for students to revisit the understandings and intentions they’d recorded on their reflection sheets from the previous assignment, with the hope that feedback from their previous work would be top-of-mind as they moved into their next assignment.

Additional Resources and Next Steps

Shortly after making these changes, I discovered Floop, an easy-to-use feedback platform that helped me further de-center grades in my classroom. Floop allows teachers to spot-annotate student work, entering notes into a comment bank and allowing you to drag and drop any comment on all submissions for that assignment. This was tremendously helpful and a huge time-saver for me. When we used Floop, I saw students implementing the suggestions I was making on their work much quicker.

Another shift I made recently was focusing less on grading individual assignments, and more on competency-based, collaborative grading. Prior to starting a unit, I lay out what we will be evaluating and describe the success criteria to my students. Students maintain their own work throughout the unit, getting feedback in the moment in class or as requested. At the end of a unit, they bring their work to a conversation with me and propose a grade on the different areas of evaluation. They are asked to support their evaluation with examples where they meet or exceed the defined success criteria. We then came to a consensus about their performance and final grade.

Unlearning and Mindset Shift

Whether you choose to implement the combination of single-point rubrics and grade delaying, move to using a feedback platform like Floop, or even start grading by conference, the innovations you implement will only transform the classroom if they are accompanied by opportunities for students to unlearn the traditional and typical grades-as-currency model. For me, this meant that I had to de-center grades as a valuable aspect of my classroom and focus more thoroughly on feedback.

This approach to a feedback-centered classroom dovetailed nicely with elements of human-centered design thinking that I was working to implement in my instruction. Encouraging iteration, privileging divergent thinking, and allowing multiple “at-bats” on a given concept or skill with designed and intentional chances to improve are all practices that my classroom features, and dispositions that foster adoption of design thinking. When my students and I began implementing design thinking practices, they were already comfortable managing ambiguity, operating with a bias towards action, and viewing problems and challenges as opportunities. I am certain this led to stronger work during their projects.

Understandably, there is hesitation with this sort of educational model. Educators have expressed concern about this approach, and to be sure, it raises many questions about student motivation and achievement. Ultimately, my experience in moving towards a feedback-centered classroom resulted in students who are more motivated by the opportunity to own their learning. Students’ agency in the evaluation of their work increased, and I had a better understanding of their ability and achievement compared to when I was collecting every assignment and grading them individually. Ultimately, I saw more growth, and my students felt more energized about completing classroom work. This tracks, as traditional approaches to grading have been shown repeatedly to have a negative effect on student motivation.

A switch in classroom technique like this can feel overwhelming, and the idea of totally revamping the way you approach student work to a conference-centered methodology can be intimidating. And that’s to be expected. But, shifting from traditional grading systems can help increase motivation and agency in students. I hope you’ll explore some of the ideas in this piece, and would love to hear YOUR feedback.

Ready to rethink teaching and learning in your community?

Contact Startland Education to hear how we can help.